Howdy! I had a different topic to write about going into this week, but a thread popped up yesterday that I really want to discuss. Apologies if that means this week’s post is a bit underdeveloped, but I hope you enjoy it nonetheless. I would also love to hear your comments!

French elections and bad fashion takes

If you’ve been on Twitter at all in the last year or so, you’ve likely seen a thread by “the menswear guy” or Derek Guy, more commonly known by his username, @dieworkwear. Usually, he is offering fashion advise regarding menswear, suits, etc., and usually doing so in response to some awful take from some other far reach of the internet.

Yesterday, he responded to far right grifter and all-around bad person Elijah Schaffer complaining about how the fashion of French leftists shows why “things are getting worse” in Europe:

In addition to undressing Schaffer’s claims (pun intended), Guy makes a great point about the morality of fashion—or lack thereof. He states: “There's no connection between clothes and morality. dressing up is also not the same as dressing well.” The link to the thread is here, and I recommend giving it (and his other posts) a read.

In response, numerous people argued quite feverishly that clothing does have a moral implication. “It’s not about the morals of the fabrics”, they say, “but about the modesty of the person wearing them. They point to pictures from the ‘50s and ‘60s as evidence of women in the past having “beautifully modest feminine glory” compared to the styles of today:

But the problem with that is that the very women pictured were dressed quite progressively for their time. The traditionalists of their era viewed their short hair as “androgynous” and their exposed legs as overly sexual.

The reality is, any time someone is talking about people dressing “modestly” or “traditionally”, they tend to just mean “dressing how they did two generations ago.” The self-proclaimed traditionalist often doesn’t yearn for traditionalism proper, but for the liberalism of their grandparents’ generation.

Women’s fashion history time

If you had asked me a year— no, a week ago if I knew anything about the history of women’s fashion, you would’ve gotten a cackle and little more out of me. I could tell you that the Victorian era was strict, and that the flappers of the 1920s weren’t, and little more.

But alas, here we are.

The website My Modern Met has a great guide to how women’s fashion evolved from the 18th to the 20th centuries. And when you skim over the images on the page, it becomes quite clear that women’s fashion has always been a battleground for debates of morality.

I’ve pulled some of the images from the site so we can take a gander below.

We start early in the age of revolutions, where the styles of the nobility and monarchies of various countries were dominant—ornate dresses, flowing gowns, and elaborate headpieces.

But over the years, we start to see gowns narrow and headpieces begin to shrink. By any modern measure, these women are all dressed quite conservatively. But compared to the prior decade, these dresses exposed far more of their wearers’ silhouettes to the world and showed off far more of their busts and necklines.

But in the mid 19th century, we see a return to the ornate dresses of the late 18th. These gowns look quite… voluptuous compared to the dresses of 1804-1811. The readoption of the corset, the protruding rear ends, and the framing of the fabric that draws attention to the wearer’s hips and breasts can be interpreted as decline in modesty. Despite the design bearing a strong resemblance to the “modest” starting point, these gowns now appear immodest when compared to the new “traditional attire” from 50 years prior.

Dead in the middle of the Victorian era, women’s gowns get slimmer still. But look at the image right above and imagine that is your standard for “traditional” attire. The tighter fitting dresses that highlight more of the wearers’ features are a major departure from the big, fluffy gowns that by then had become “traditional”.

And still, the men and women who became accustomed to the dresses above went apoplectic in the aftermath of World War I. Women started cutting their hair short and—shockingly—showing their ankles! The “masculine” bob cut gained prominence and exposed ankles/lower calves became commonplace. But eventually, this progressive fashion would become the traditional fashion of later years, just like all of those “scandalous” outfits that came before.

Cue the 1960s—the time that Elijah thinks women were dressed with “beautiful modest femininity”. Gaze in horror at the exposed kneecaps, the uncovered shoulders, and the free-flowing hair. Compared to prior decades, these women were androgynous, rebellious trollops. And when the 1970s roll around and women start wearing pants more frequently? It’s enough to send a 1920’s flapper into shock!

It’s not just women’s fashion, either

…

One of the people arguing in that original thread that fashion is about modesty is pictured above on the left. As Guy points out, the very jacket that this “traditionalist” man is wearing was once the symbol of youth rebellion:

After the 1947 Hollister riot, people in small, conservative towns believed that roving motorcycle gangs were going to ruin their neighborhood. Youths wore black leather jackets to strike a rebel pose against the Establishment, which was represented by the Man in the Grey Flannel Suit.

This man falls into the same line of thinking we talked about regarding women’s fashion: what used to be rebellious and progressive becoming accepted and eventually “traditional”.

And like women’s fashion, menswear can often follow circular patters. What is “feminine” today may just have been the masculine attire of yesteryear.

Imagine a young boy wearing a dress. That kind of screams progressive, doesn’t it? I can see it now: Libs of TikTok posting about how the “woke left is transing kids” because a boy is wearing a dress.

Except Teddy Roosevelt, perhaps the most “traditionally masculine” President we’ve ever had in the United States, looked like this as a child:

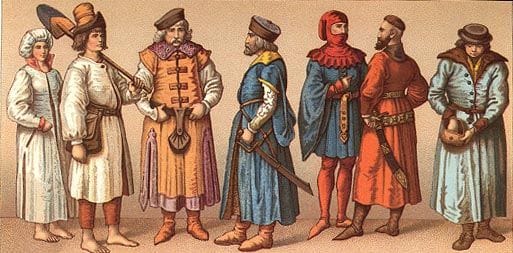

And while a man wearing a dress today might face slander and slurs calling him weak, woke, or gay, this is what the hard working male peasants of Europe looked like 700 years ago:

And here’s how their nobles and knights dressed when not on the battlefield:

It’s hardly what anyone today would call “traditionally masculine”, but men dressed like this likely killed more people in combat than any man you’ve met in your life.

In reality, fashion has always been changing. People who crow about the “immodesty” and “androgyny” of young women or the “rebelliousness” and “femininity” of young men reflect a fear that every generation has as they age: that the youth seems to be in a pattern of moral decline.

But that perception is just plain incorrect.

The kids are alright; we just love to be afraid

The website Pessimists Archive has a great timeline that highlights news clippings from the past, clearly showing the moral panic that comes around with every significant cultural or technological shift.

From the epidemic of reading books in 1904:

…to Jazz music being blamed for increases in suicide in 1924:

… to the alleged corrupting “evil” of comic books in 1955:

… generations of parents have always feared what their kids are getting up to, and who the next generation is becoming.

Psychologist and science writer Adam Mastroianni writes that an overwhelming percent of the population surveyed consistently says that morality is declining:

But when studied further, that perception never shows up in how people view the morals of the society in which they live. Essentially, they think morality is declining, but they also think that society is just as moral as their parents thought their society was:

Other surveys asked questions like “Were you treated with respect all day yesterday?” or “Are people generally helpful, or are they only looking out for themselves?”, yielding incredibly consistent answers: about 90% feel respected and about half of people think that others are generally helpful. These numbers haven’t changed much if at all over the past 20 years.

So what gives?

It’s well known by now that humans have an evolutionary instinct toward fear, even if nothing is wrong. After all, our ancestors who didn’t sense the tiger lurking in the bushes wound up dead. This evolutionary ability to constantly think about possible negative outcomes has kept our species alive, but it’s also caused us to have a deep-seated, unexplained sense of anxiety about the future.

This is known as negativity bias, and is related to something called Prospect Theory, popularized by Nobel laureates Daniel Kahnemann and Amos Tversky. In their seminal paper “Bad is Stronger Than Good”, Roy Baumeister and Ellen Bratislavsky showed that we feel and fear loss far more than we feel and desire gain.

Kahnemann and Tversky explain that the pain of loss is greater in part because we evaluate whether something is good or bad from an adapted reference point. We don’t judge good and bad from some universal truth, but relative to the “neutral” that is determined by our own experiences. We fear the future because we fear losing the things we cherish, and the promise of even better things to come isn’t enough to make us feel better.

In their fear, parents look to how their parents and grandparents lived as the baseline for how young adults should live. They think back to their happy childhoods and nostalgic memories and set a benchmark for what neutral is, based on all of the things they hold dear. And when they compare the real, human current generation to the idealized, rose-tinted version of generations past, they will inevitably view the youth as failing to measure up.

The promise of the new great things future generations can do pales in comparison to the fear that they will stop doing the good things we love.

But if anything, we are a kinder society today than we were a hundred years ago—women and minorities can vote, institutionalized discrimination is on the decline, and charitable giving is at an all-time high:

The future your great-great-grandparents feared is better than the present they lived in. The same goes for your grandparents. And the same goes for you.

So when you see some new trend popping up online, leave your pearls alone and take solace in the fact that the kids will be alright. And if you see someone else freaking out about the “moral decline of society”, it’s usually a good idea to check if they are ignorant or have some political (or discriminatory) agenda.

How was this post?

Extra, extra!

Speaking of great things that young adults have done, Willow (yes, Will Smith’s daughter) has released what may be my favorite song of the year so far. If you’re a music nerd, you’ll probably enjoy the switch from 7/4 time in the verses to 4/4 in the chorus. It feels like this weight lifts and you’re flying.