Who becomes a dictator?

It's a question worth asking when a dictator falls. What kind of person looks at the historical record—the exiles, the assassinations, the mob violence, the palace coups—and thinks, "Yes, I would like to try that"? What internal calculus produces someone willing to watch their country disintegrate rather than relinquish power? And what does that leader's absence mean for their country?

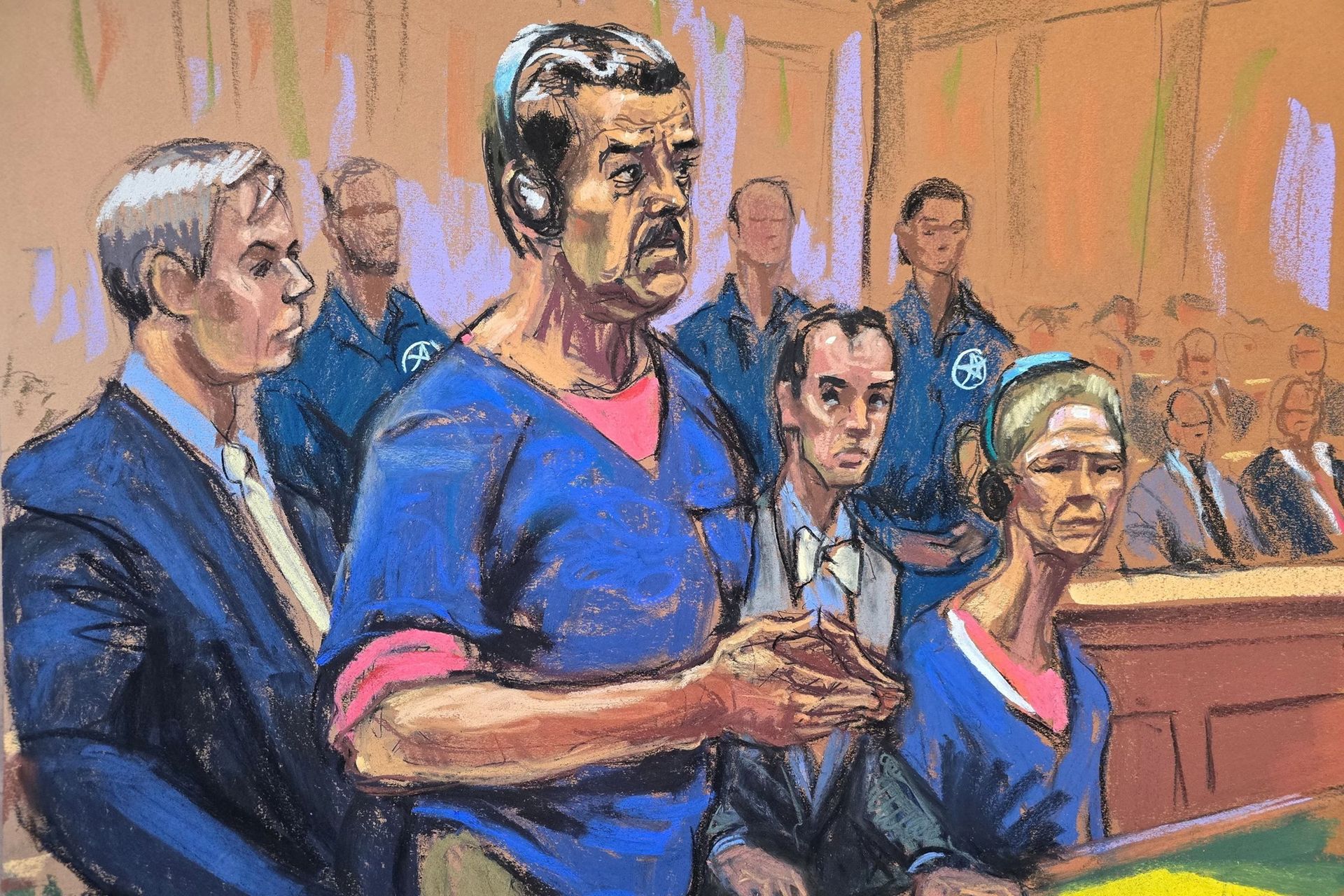

Nicolás Maduro is now in American custody, which means we'll get to observe one data point up close. The man who starved Venezuela while lecturing the world about imperialism, who jailed opponents while praising his faux democracy, who presided over an economy so fictional that his government's GDP figures bore no relationship to what satellites could literally observe—that man will now answer questions in a New York courtroom instead of a Caracas palace.

Good. Let's examine how we got here, and why it might matter.

Dictators and the Dark Triad

Sociologist Brian Klaas has observed that leaders display the "dark triad"—narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism—at rates far exceeding the general population. The conventional wisdom holds that power corrupts, but Klaas suggests the causation runs the other way: Corruptible people seek power in the first place. The selection mechanism for political leadership risks filtering for exactly the wrong traits. This is especially true when checks and balances fail to distribute power properly, and the draw of ultimate control pulls in malefactors.

Maduro is a textbook case. He inherited a revolution already cannibalizing Venezuela's economy, doubled down on every policy that wasn't working, and refused to acknowledge reality even as eight million citizens fled the country. The "dictator's information problem"—the phenomenon where questioning the official line becomes so dangerous that leaders never learn when things go wrong—meant he was governing a fantasy while the actual country collapsed around him.

"In actual planned economies," notes economist Arnold Kling, "we have seen social morale degenerate while cynicism and corruption spread." Venezuela proved the point with brutal efficiency. Chávez and Maduro built an economy on the premise that central planning could substitute for market prices, that revolutionary zeal could substitute for innovation, and that narcotics trafficking could substitute for a viable economy. They got all three wrong, and millions suffered for it.

It is good and right that Maduro is gone. But I understand the hesitation some feel about how it happened.

The Precedent That Matters

The Iraq comparison is already everywhere—cable news, Twitter, the usual suspects warning about blood for oil. It's the reflexive historical rhyme whenever American forces remove a foreign leader, and it oversimplifies the situation to the point of distortion.

The Iraq war was an exercise in maximalist ambition. The Bush administration didn't just want to remove Saddam Hussein; they wanted to transform Iraqi society, install democratic institutions, and use that transformation to reshape the entire Middle East. It was hubris dressed as idealism, and it failed catastrophically.

A more fitting precedent is Panama in 1989. George H.W. Bush ordered Operation Just Cause and captured Manuel Noriega, who was under federal indictment for drug trafficking. Panama held elections. Democracy took root. American forces went home. It wasn't pretty, but it worked. And while corruption still runs rampant through Panama's government, life has objectively improved for the Panamanian people.

Like Noriega, Maduro faced federal drug charges. Like Noriega, he ran a criminally corrupt regime that violently suppressed democratic movements. Like Noriega, his removal created space for legitimate governance rather than imposing a new order from outside.

Both Noriega and Chávez pioneered a playbook that authoritarian leaders around the world have since copied: Use anti-colonial rhetoric to camouflage what is actually just socialism and corruption. Wrap yourself in the flag of the oppressed while oppressing your own people. Blame America for every failure while your cronies get rich. Other countries struggle with corruption, political dysfunction, and the impartial application of the law. But Chavismo didn't just struggle with those things—it actively opposed them as bourgeois obstacles to revolutionary justice.

Maduro's removal matters because it creates the possibility—not the guarantee, but the possibility—that Venezuela could join the community of nations that at least aspires to lawful governance.

Maduro's capture has the potential to mimic the success of Operation Just Cause: a targeted removal of a criminally indicted drug trafficker who happened to be running a country—no occupation, no nation-building, no lasting commitment to spending American blood and treasure in a foreign land. But Trump has already begun undermining this best-case scenario. He's talked about the United States "running" Venezuela. He's posted about extracting Venezuelan oil for American consumption. He's discussed inviting American oil corporations back into the country. These are not the statements of a president planning to get out of the way. These are the statements of a president who sees Venezuela as a prize to be claimed.

The Execution Problem

The man who ordered Maduro's capture displays his own version of the dark triad. Donald Trump's narcissism is legendary. His transactional approach to relationships, his inability to admit error, his instinct to personalize every conflict—none of this is news. His supporters have decided these traits are features rather than bugs. His critics have been pointing them out for a decade.

This administration has demonstrated, repeatedly and consistently, that it cannot execute complex operations requiring sustained attention and institutional competence. They alienate allies. They staff critical positions with loyalists rather than experts. They get bored when the cameras move on. They tweet inflammatory nonsense at precisely the wrong moments. They pick fights over trivial matters of ego while substantive issues languish.

The capture of Maduro was the easy part. What comes next is hard.

Venezuela's economy has been systematically looted for two decades. The infrastructure is destroyed. The diaspora is scattered across Latin America. There is no clear leader who can step up besides Maduro's lieutenant, Delcy Rodríguez. The military and militia are riddled with Chavismo loyalists. Russia and China have billions invested and won't simply accept a pro-American transition.

Managing all of this requires patient, boring, unglamorous diplomacy. It requires resisting the urge to turn Venezuela into a campaign prop. It requires working with regional partners—Brazil, Colombia, Caribbean nations—who have their own interests and sensitivities. It requires, in short, exactly the kind of institutional competence this administration has never demonstrated.

But the deeper problem isn't institutional—it's psychological. The narcissist who announces he will "run" Venezuela cannot conceive of an outcome where he isn't the protagonist. The Machiavellian who muses about extracting oil cannot resist treating a humanitarian intervention as a business opportunity. The man who has spent his entire life believing he can will reality into existence through sheer assertion cannot accept that Venezuela's problems require patient, self-effacing work rather than dramatic declarations of victory.

This is the mechanism by which good operations yield bad outcomes. The initial strike was sound. The legal justification, while debatable, has precedent. The immediate result is positive. But every day that Trump pushes for American control rather than Venezuelan self-governance, every statement about oil extraction, every hint that this is about American interests rather than Venezuelan freedom, the operation drifts further from Noriega and closer to Iraq. The elder Bush succeeded in Panama because his administration understood that the point was to leave. This administration, much like the younger Bush's, shows every sign of believing the point was to stay.

"If your position boils down to 'norms for thee but not for me,'" Jonah Goldberg has observed, "you don't actually believe in norms." This administration has treated norms as obstacles to be overcome rather than constraints to be respected. That approach might work for capturing dictators. It's catastrophically ill-suited for building stable post-authoritarian orders.

The George Washington Question

There's a telling contrast in the history of the Americas. George Washington voluntarily relinquished power—twice. He declined a third term as president and rejected any suggestion that he should be king. "That was unusual, unlikely—exceptional." It established the precedent that American leaders would submit to democratic accountability.

Simón Bolívar, the liberator of much of Latin America, took a different path. Out of a belief that Latin America was not ready for democracy, he a became a caudillo. The tradition he established was one of strongmen claiming power for themselves rather than transferring it peacefully. Venezuela has never fully escaped that tradition. And the current leader of the United States seems more sympathetic to it than to the American one.

The question now is whether Maduro's removal will produce something closer to the Washington model—peaceful transfers of power, institutional constraints on executive authority, leaders who submit to law rather than embodying it—or whether it will simply produce a new strongman claiming legitimacy from the intervention that installed him.

The precedent set by this operation may matter more than the operation itself. Is this a return to thoughtful regional engagement, or the beginning of a new era of hemispheric intervention? The answer depends largely on how the administration handles the aftermath—and on whether they can resist their own worst instincts long enough for Venezuelan institutions to take root.

Constitutional Considerations

What also matters is the method by which Trump executed this removal. One can argue this was simply criminal justice—enforcement of the law against an indicted narco-trafficker. But you cannot ignore that Maduro was the leader of a sovereign nation. A military action of this magnitude demands some coordination with—or at least notice to—allied governments and other branches of our own government.

At minimum, committing what can be described as an act of war without notifying Congress, the branch constitutionally empowered to declare war, reveals Trump's own strongman tendencies laid bare.

The backlash has been deserved to some extent. Trump has limited constitutional authority for military actions like this. I've seen compelling arguments that this may have skirted just within his purview as an exercise of law enforcement, but I'm uneasy. And his unsubtle threats toward the leaders of Colombia, Cuba, and even Denmark give me serious pause.

Some have responded with lines like "Now Russia has a free pass to kidnap Zelensky" or "Now China has cover to interfere with Taiwan." Let me be clear: they were already doing those things. The concern isn't that this action might incentivize other major powers to act recklessly—they already were. The threat is that Trump himself may feel the draw of a new manifest destiny, a new colonialism. The real risk is that his appetite for regime decapitation may have been whetted rather than sated.

Where We Go From Here

Maduro deserves to face justice. The Venezuelan people deserve a chance at something better than the grinding misery they've endured for a generation. And the Noriega precedent that critics dismiss too quickly offers a real model for success. Panama is a functioning democracy today. Indonesia moved on from Suharto's dictatorship and has since regularly had peaceful transfers of power. Post-authoritarian recoveries happen. They require patience and restraint, but they happen.

The threat to this outcome isn't American power or intervention as a concept. It's not Venezuela's complexity or the challenges of rebuilding a looted economy. The threat is specific and personal: Donald Trump's apparent inability to let a good outcome speak for itself.

If Trump can follow the elder Bush model—support elections, defer to regional partners, resist the urge to extract resources or claim permanent credit—Venezuela could join Panama in the success column. If he can't, if his psychology compels him to turn a humanitarian intervention into an imperial project, then he is bound to watch his popular military action curdle into an unmitigated disaster.

Venezuela's future is genuinely open. That's more than could be said a week ago. And that's worth something—even if the man who made it possible is the greatest risk to its realization.